Original Tweetstorm: https://twitter.com/avichal/status/1238298350077669377

I’m sharing lessons from running a startup through 2008. I tweeted this as well and cleaned up a bit for the blog. Hope it’s useful to founders.👇

1/ Most important — prioritize your health and family. It’s clearly stressful as the world feels like it’s falling apart. If you are healthy and have your loved ones, you will be fine long term.

2/ Duration — this will last a lot longer than you expect. From peak S&P in 2008 to bottom was 500 days. We are only 20 days in to this correction. Maybe it’s different this time…more likely we have a long way to go. And it will feel a lot worse than it does right now.

3/ Cut costs faster and deeper than your intuition suggests — cutting costs is hard but probably the best way to extend your runway. Letting people go is *very* hard. But if you are forced to, cut once + deeply so you never cut again and no one else is worried about their job. Make it clear to your remaining team members that you have cut so deeply so that you never have to come again.

4/ Be patient on hiring — Hire slowly. Many talented people may be available in a year and companies that have strong cash positions will aggregate amazing people, which will be a long term competitive advantage. The best people will want to work with the best people, especially in a downturn where talent aggregates in a small number of places.

5/ Revenue often falls as a second order effect — It takes time for the second order effects of unemployment, leverage leaving the system, businesses cutting back, governments losing tax revenue, etc. to materialize. Your revenue may be fine now but may not be in 6 months.

6/ Help people stay long-term oriented — spouses will lose jobs, friends will worry about layoffs, more people will be sick bc they are stressed, etc. Help people think about focusing on creating long term value. If you have cut deeply enough, you should be able to survive. This will give you emotional energy to support others.

7/ Reputations are made or lost in times like these — people will talk about these crazy times in a decade. Your peers, your investors, and your employees will remember how you behaved on the way down and in tough times. Never lose your integrity or make rash decisions.

8/ Negotiate — you’d be surprised how much leverage a macro turn will give you. You can probably negotiate a lot of things in your business life. Do not negotiate at the expense of long term relationships and integrity. But if you need something, ask.

9/ Deals & contracts will fall apart — Contracts are only as good as the people signing them. Investors may pull out after giving you a terms sheet. Partnership agreements may be cast aside. Landlords may change terms. Be ready for people to back out of signed contracts.

10/ Fundraising will slow down and pick up in 6 mo — Late stage doesn’t want to catch a falling knife and early stage investors know that only companies that have to raise are raising now. Both drive down valuations. But eventually investors have to invest, so they will. In my experience, uncertainty drives people to pull back and be more conservative, and investors know startups that can avoid fundraising in uncertain times will wait. Those who cannot wait are the ones raising now, so investors have more leverage in the short term.

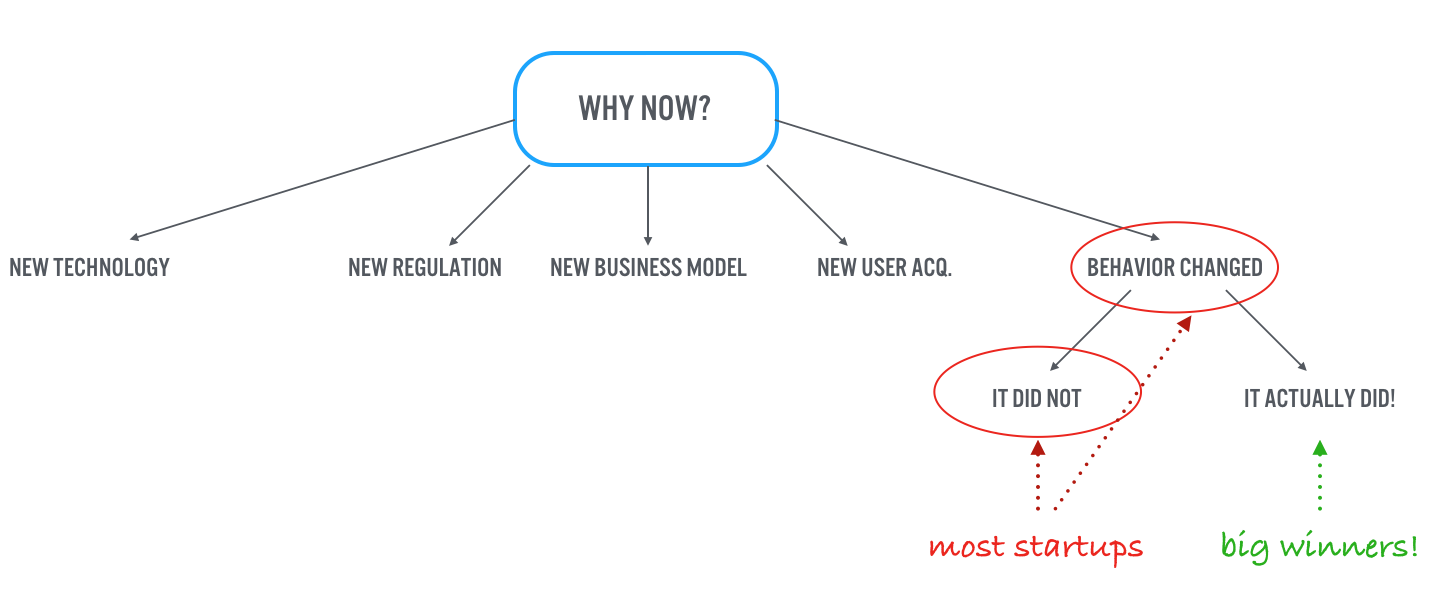

11/ There will be monster businesses built soon! Many of the best businesses scaled in 2008 or 2001. Google, Facebook, Airbnb, etc. A correction accelerates behaviors, i.e. share economy scaled in 2008 b/c people needed extra cash. Remote work & crypto are my bets for this one

12/ Remember: Few events are as good as they seem in the moment and few as bad as they seems in the moment.